Custom Multiplayer Networking in Godot

Organization

Chasing Carrots

Game

Unannounced Title

Date

2025

Duration

4 Months

I spent four months deep inside multiplayer networking in Godot while working with Chasing Carrots on their upcoming co-op project. The goal was simple. Can we replace Godot’s built-in multiplayer layer with a custom system that gives us more control, more flexibility, and better support for peer to peer features? This post is about what we needed, how I implemented it, and how it went. For most parts the code was written in C++, as I worked inside the Godot Engine source code and the Epic Online Services Godot extension. I learned a lot about debugging foreign code and how to navigate in large code bases.

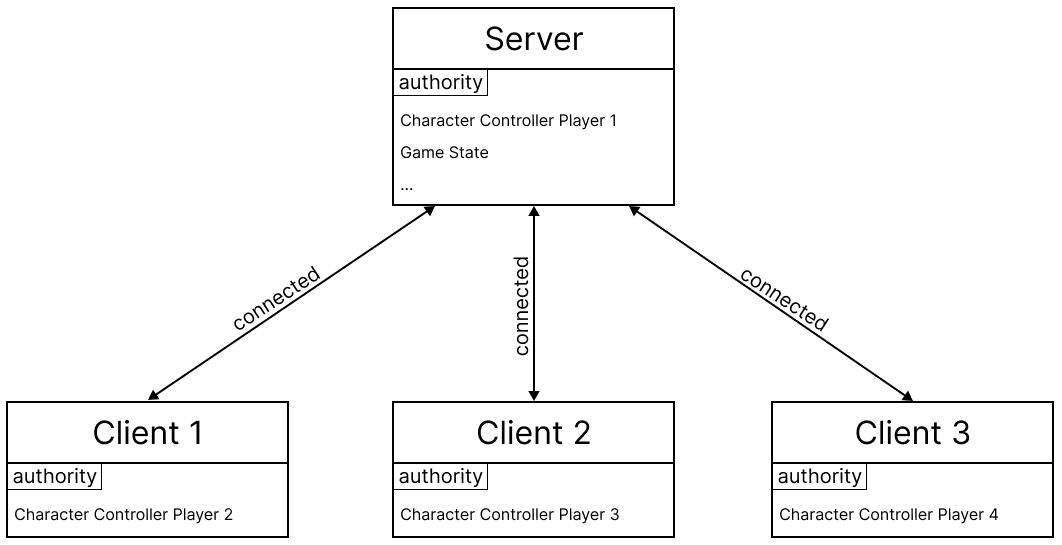

The problem with the default model

Godot’s multiplayer stack is great for getting started. You can spin up a networked prototype in minutes. RPCs are easy. Synchronization is built in. For small projects, it is honestly hard to beat. The trouble starts when a project grows. Our game already had a classic client to server architecture. Every client talked to a single server peer. If one client wanted to send data to another, the packet went through the server first. That extra hop adds latency and increases server load. For gameplay it is manageable. For voice chat and fast input updates it is not ideal.

We also wanted to move away from heavy reliance on Godot specific helpers like MultiplayerSpawner and MultiplayerSynchronizer. They work, but they push you toward a very specific architecture. The studio needed something more modular and closer to the transport layer.

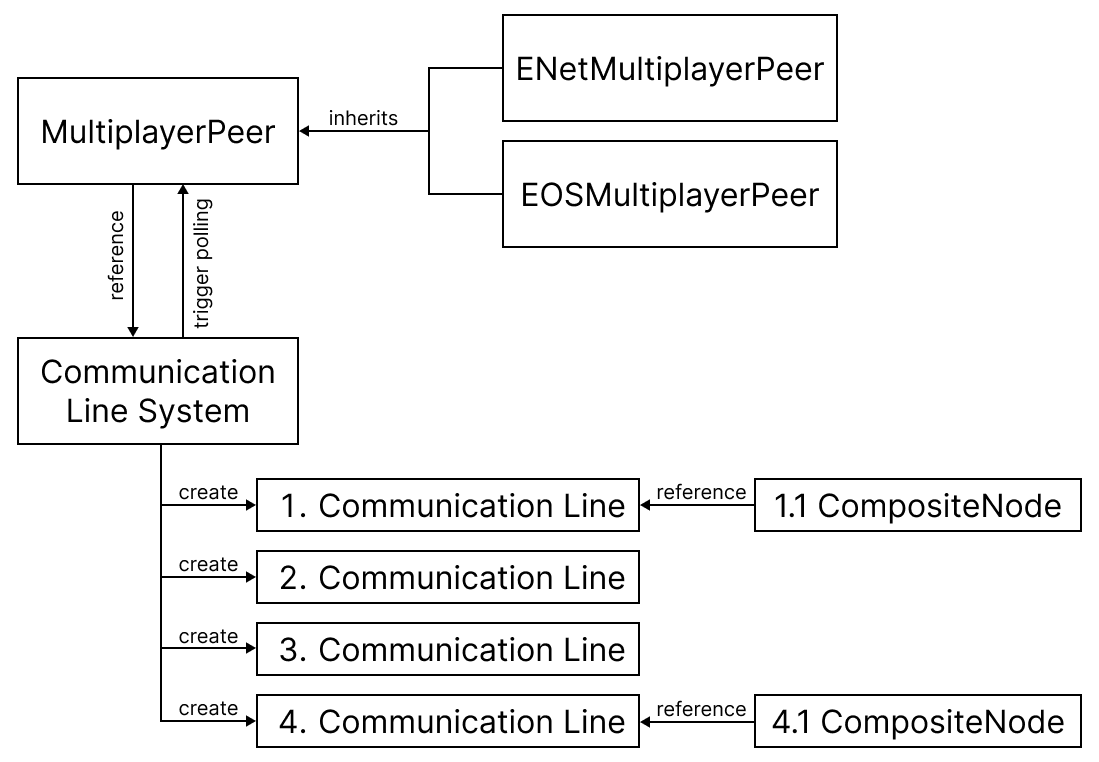

The Communication Line System

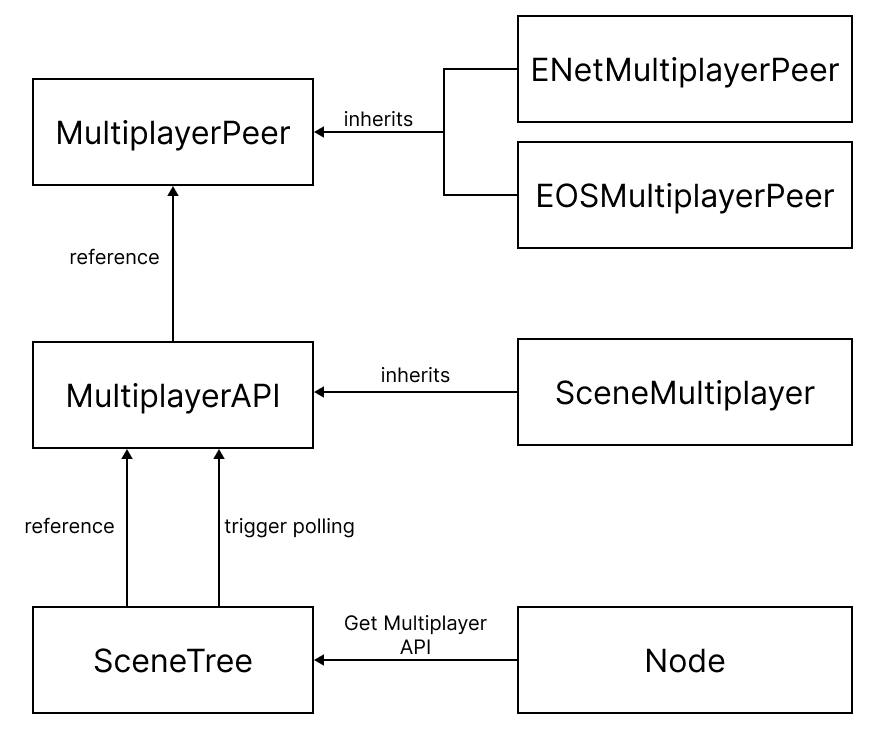

The answer was a custom framework we call the Communication Line System, or CLS. Instead of building on top of Godot’s RPC layer, CLS talks directly to the MultiplayerPeer. It acts as a lightweight message routing system that lives alongside the engine rather than inside the default MultiplayerAPI.

A few design goals guided the system:

- Multiple independent CommunicationLineSystems can exist at once

- Packages can be filtered using bitmasks

- Authority is handled explicitly

- Networking code does not depend on scene structure

Instead of sprinkling RPC calls across dozens of scripts, we route everything through structured communication lines. That makes it easier to reason about what travels over the network and who is allowed to send it.

Refactoring away from MultiplayerAPI

The first real task was ripping out our dependency on Godot’s MultiplayerAPI. Previously, the Communication Line System still used the API internally to access the peer and poll data. I rewired it so CLS owns a direct reference to the MultiplayerPeer. Polling is now handled inside our own code, using a stripped down version of Godot’s internal networking loop. Authority was another big change. Godot assigns authority by peer ID. We replaced that with a bitmask based system. The first bit represents authority. Messages can be filtered by checking these bits, which makes routing flexible and cheap.

I exposed new helper functions to GDScript so gameplay code can ask:

- is this peer the authority

- who currently holds authority

- is this peer the server

Once that was done, I migrated a full test project. Every RPC call was replaced with CommunicationLine calls. All MultiplayerSpawner and MultiplayerSynchronizer usage was removed. The test scene synchronized dozens of data types at regular intervals and displayed them in a debugging window. If anything desynced, it would show immediately. After the refactor, the scene behaved identically to the old implementation. That was the first big milestone.

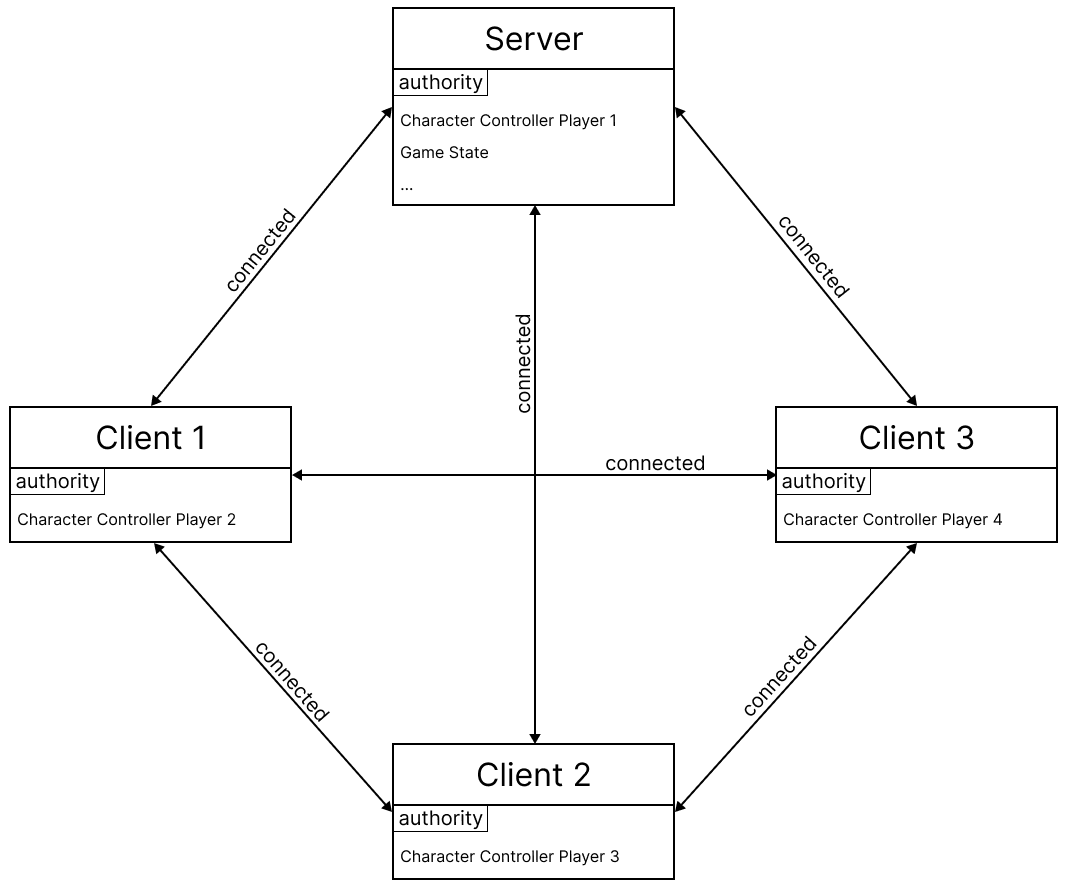

Building a peer to peer mesh

The next step was building full network meshes. In a mesh, every client is directly connected to every other client. You still keep a logical server for authority and coordination, but data does not need to bounce through it.

This matters a lot for proximity voice chat. Audio packets can travel directly between players. That reduces latency and removes unnecessary server load.

I implemented meshes for two backends:

- ENet for fast local testing

- Epic Online Services for shipping

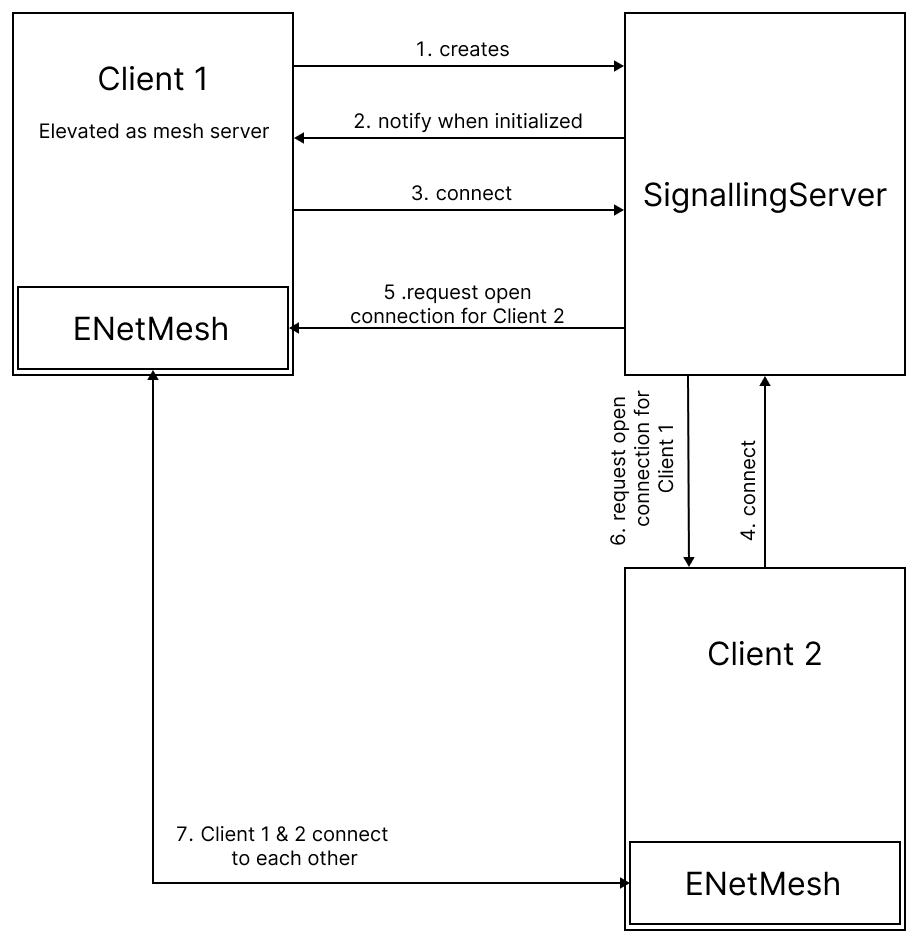

ENet mesh

ENet does not give you discovery for free. I had to build a signaling server that hands out IP addresses, ports, and peer IDs. Each peer to peer link needs its own port. You cannot reuse a single port for multiple ENet hosts. The signaling server tracks which ports are in use and distributes them safely.

Once both clients open their hosts and acknowledge the connection, we register the link with Godot using add_mesh_peer. At that point the engine recognizes the peer and CLS can route messages normally. Testing confirmed that clients could send packets directly to each other without touching the server. That was the proof that the mesh actually worked.

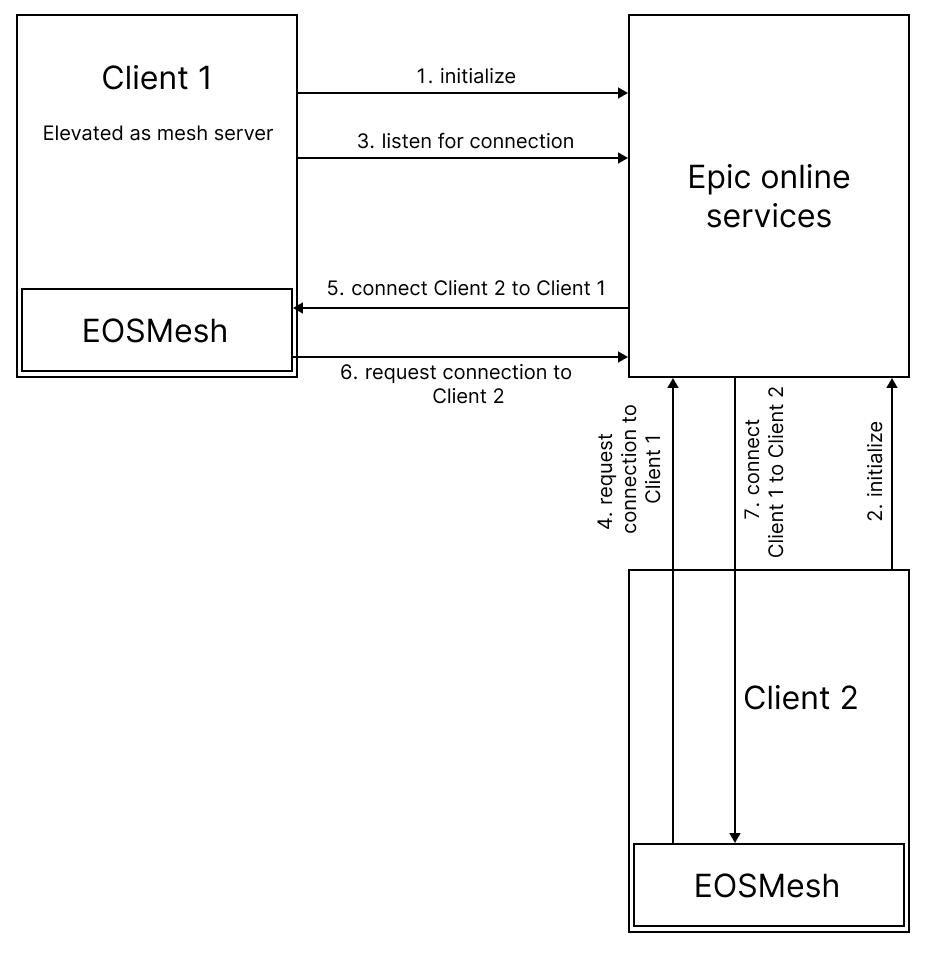

EOS mesh

EOS handles discovery internally, so the setup is cleaner. Clients log in, exchange user IDs, and call add_mesh_peer using those IDs. In practice, everything worked until I tried running two meshes in parallel. One mesh for gameplay. One mesh for voice chat. The second mesh silently failed on one client. The connection request never showed up. Debug tools confirmed that one side believed the peer existed and the other side did not.

After days of stepping through the EOS extension code, I found that the request was likely being swallowed inside the SDK. I could not fix the root cause, so I implemented a workaround. The client repeatedly sends connection requests until confirmation arrives or retries run out. It is not pretty, but it works. Both meshes now register correctly, and voice chat came back to life.

Integration and real playtests

The final step was merging everything into the main project. This was less glamorous than the research work.

It was a long cleanup pass:

- replacing every remaining RPC

- removing MultiplayerAPI helpers

- rewriting authority checks

- Rewriting CLS initialization

Once integrated, the team ran a full studio play session. Everyone connected and completed a full run. Compared to earlier builds, the connection felt more stable and responsive. It is not perfect yet. Later tests still revealed disconnect issues. We cannot say for sure whether those are caused by the new architecture or by unrelated systems. What matters is that the foundation is now flexible enough to debug and extend properly.

What this actually changed

The biggest win is not raw performance. It is control. We now own our networking layer. We can run multiple meshes. We can route messages without fighting the engine. We can build features like proximity voice chat without bending the architecture into strange shapes. The cost is complexity. A custom system always carries maintenance overhead. But for a cooperative multiplayer game that depends heavily on networking, the tradeoff is worth it. Future work will focus on stress testing. We want to see how the system behaves under heavy packet loss, latency spikes, and large amounts of synchronized data. The current implementation is a strong foundation, not a finished solution.

Final thoughts

This project forced me to read and modify large chunks of engine code, debug third party extensions, and design networking architecture that survives real production constraints. It was frustrating at times, especially when a bug hid for days before revealing itself. It was also one of the most rewarding technical deep dives I have done. The game is still in development, but I am glad that part of its foundation now carries my fingerprints. If nothing else, it proved that Godot is flexible enough to support a fully custom multiplayer layer when a project demands it. And sometimes, that is exactly what you need.